When Disasters Strike, Emergency Response Slows. Here’s Why.

When a cyclone makes landfall or a bushfire sweeps through a region, emergency services are immediately thrust into some of the most challenging conditions they will ever face. Sirens still sound, phones still ring, and crews still deploy. Yet response times often slow, access becomes difficult, and help does not always arrive as quickly as communities expect.

This is not because emergency responders are not doing their jobs. It is because natural disasters disrupt the systems that emergency response depends on. Australia’s experience with cyclones and bushfires shows that during extreme events, emergency services are forced to operate in an environment where demand surges, infrastructure fails, and risks multiply at the same time.

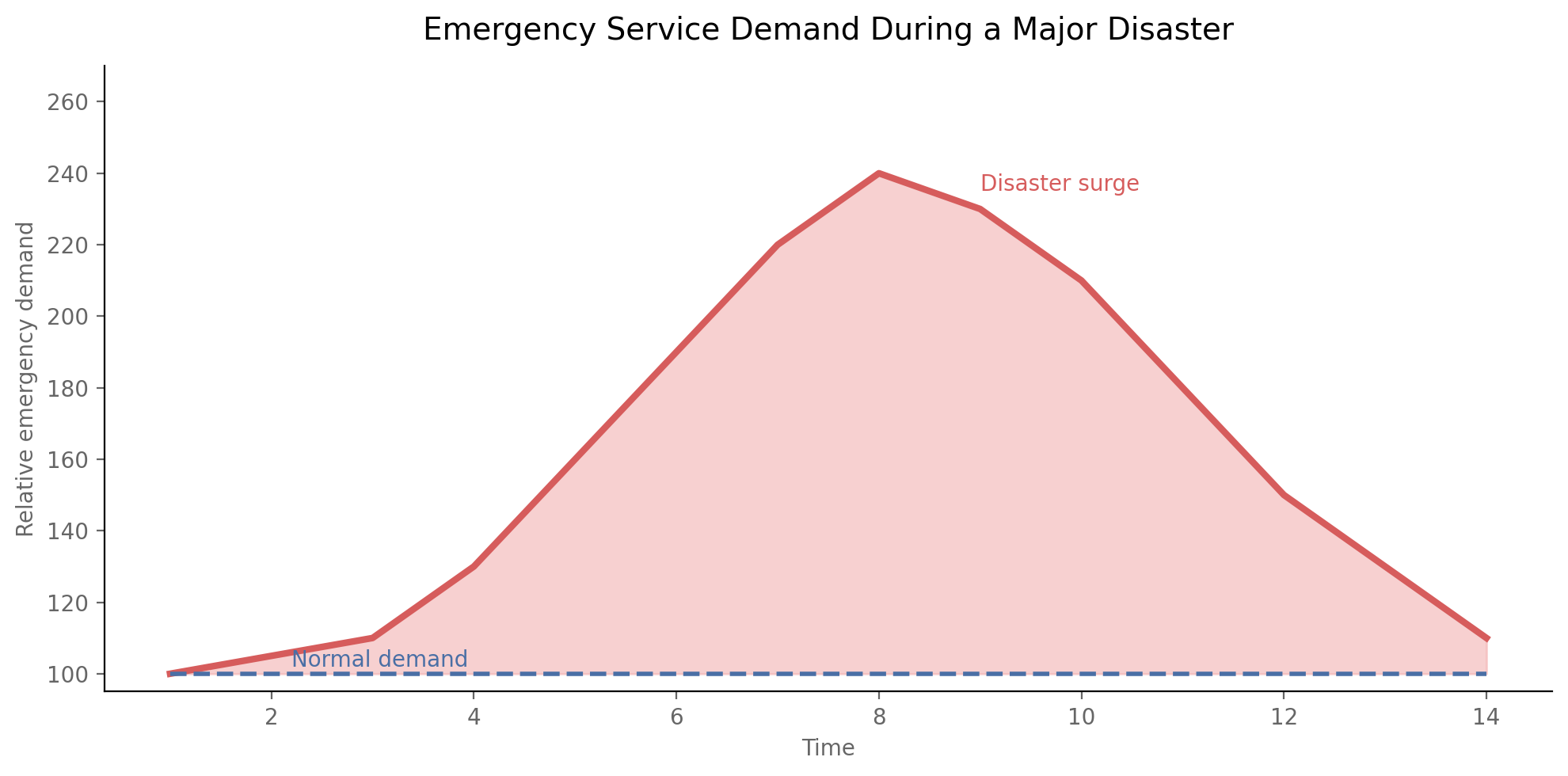

A surge in demand that changes the game

On a normal day, emergency services respond to a steady stream of calls for medical emergencies, accidents, fires, and welfare checks. These calls follow relatively predictable patterns.

During a disaster, that predictability disappears.

Cyclones generate widespread emergencies across large geographic areas. Ambulance services respond to injuries during evacuations, flood rescues, and medical complications caused by power outages, while routine emergencies continue in the background.

Bushfires place similar pressure on the system, often over much longer periods. Fire agencies fight active fire fronts, police manage evacuations, and ambulance services treat smoke-related illnesses and injuries, all while responding to unrelated emergencies.

Former NSW State Emergency Service deputy director general Dr Chas Keys has warned that these compounding demands are becoming more common. He has said that slower-moving storms and more intense rainfall events “significantly increase the threat to life,” particularly when emergency resources are already stretched across multiple incidents.

Dispatchers are forced to make constant decisions about which calls receive immediate response and which must wait. Triage becomes relentless.

When access disappears

Emergency response relies on a basic assumption: crews can physically reach the people who need help. Disasters regularly break that assumption.

Cyclones bring floodwaters, fallen trees, landslides, and damaged bridges. Ambulances may be available but unable to reach isolated homes. Fire appliances can be cut off by rising water or debris. In some cases, responders must wait for conditions to improve or rely on boats or aircraft, which are limited resources.

Bushfires present a different set of challenges. Roads are often closed due to active fire fronts, falling trees, or dangerous smoke conditions. Entire communities can become inaccessible, even to trained emergency crews.

David Templeman, former director general of Emergency Management Australia, has previously noted that disasters expose how quickly normal access assumptions break down. He has said communities are often surprised by how rapidly conditions change and how limited emergency access can become once infrastructure is compromised.

Communication under strain

As access becomes more difficult, communication often deteriorates at the same time.

Cyclones can damage mobile phone towers, cut power to communication hubs, and interrupt internet services. Bushfires can destroy infrastructure in rural and forested areas where redundancy is already limited.

The Bureau of Meteorology regularly embeds meteorologists in state emergency control centres during severe weather events to help incident controllers make decisions as conditions evolve. But even with expert forecasting support, damaged communications can slow the flow of information between dispatchers, crews, and the public.

When communication systems falter, emergency response becomes less precise. Dispatchers may receive fragmented information. Crews may struggle to relay updates from the field. Public warnings can be delayed or missed entirely.

The complexity of coordination

Large disasters demand coordination between fire services, ambulance services, police, state emergency services, health agencies, local councils, utilities, and transport authorities. Each organisation has different responsibilities and command structures.

Australia’s Chief Scientist, Professor Alan Finkel, has repeatedly emphasised that disaster resilience depends on strong coordination and shared understanding across agencies. He has argued that better integration of science, forecasting, and planning improves decision-making, but only if systems are designed to work together under pressure.

During cyclones and bushfires, that pressure is constant. Information is incomplete. Conditions change rapidly. Decisions carry serious safety consequences for both the public and responders.

Managing coordination becomes a major operational task in itself.

The human limits of response

Emergency services are staffed by people, not machines.

Bushfires often require weeks of sustained operations. Crews work long shifts in dangerous conditions, exposed to heat, smoke, and traumatic scenes. Fatigue builds, affecting physical endurance and decision-making.

Cyclones may be shorter events, but responders often work around the clock before and after landfall. Many are dealing with damage to their own homes or concern for their families while continuing to respond professionally.

Emergency services plan for surge capacity, but no workforce can operate at maximum intensity indefinitely.

Why normal response times no longer apply

Response time benchmarks are designed for everyday conditions. They assume clear roads, functional communications, and manageable call volumes.

Cyclones and bushfires remove all three assumptions at once.

During disasters, emergency services shift focus from speed to survival. They prioritise immediate threats to life, manage risks to responders, and adapt continuously as conditions change.

Response times still matter, but they cannot be interpreted in isolation.

Pressure, not failure

Reviews of major Australian disasters consistently show extraordinary effort by emergency responders working under extreme conditions.

What cyclones and bushfires reveal is not a failure of emergency services, but the reality that no system can operate at full capacity when demand surges everywhere, infrastructure is damaged, access is restricted, and operations are sustained over long periods.

Understanding these constraints helps explain why disaster response looks different from everyday emergencies and why preparedness, resilient infrastructure, and realistic expectations matter long before the next disaster arrives.

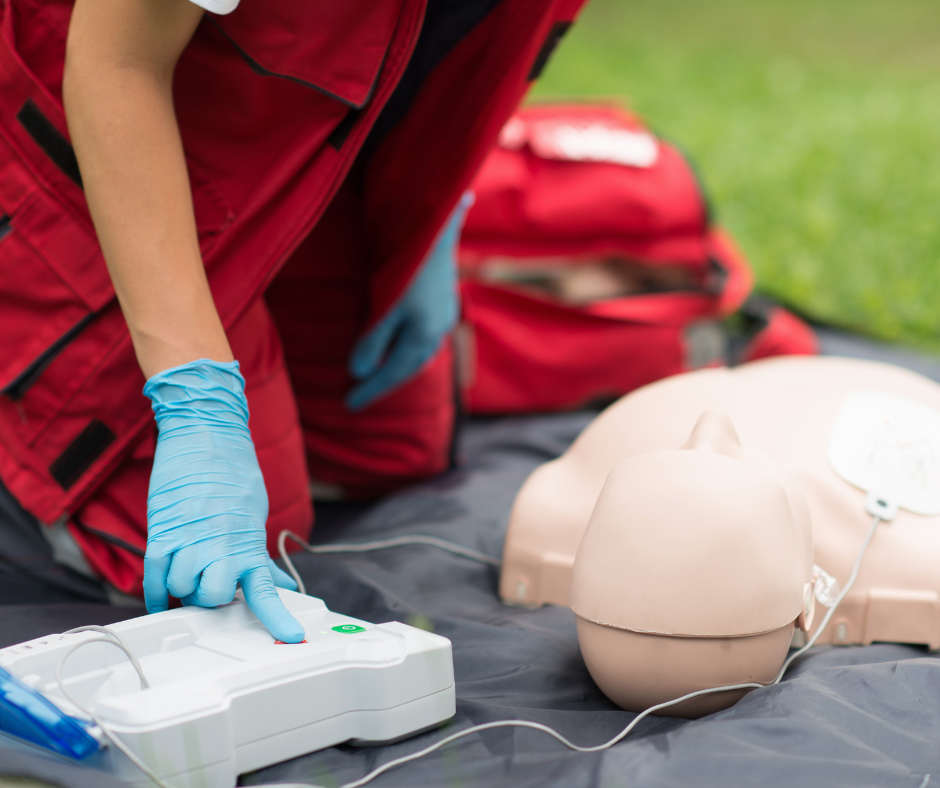

Being prepared before an emergency happens can make a critical difference. First aid training is one practical step individuals and communities can take to be ready for both natural disasters and everyday medical emergencies.

Courses are available at Find Training

Share This Article:

Articles, Updates & Announcements

from Allen’s Training

Read More

What Life-Saving Looks Like in 2026

As Australia enters 2026, the way lives are being saved is quietly changing. The most important moments in a cardiac emergency are no longer defined by the arrival of paramedics alone. Increasingly, they are shaped by what happens in the first few minutes, and by who is already nearby....

Continue Reading

Celebrating Excellence: Talk Smart Training Wins Regional Training Champion Award

Continue Reading